| Back To Clips | ||

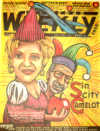

(EDITOR’S NOTE: This was the first in-depth magazine profile ever published on Carolyn Goodman, who was elected to succeed her husband Oscar as mayor of Las Vegas on June 7, 2011. Two stories follow: cover piece, 'Sin City Camelot,' immediately below, and sidebar, 'Highbrow For The Masses?')  Sin City Camelot By Chuck Nowlen She was the highbrow Manhattan princess, the silver-spoon achiever. He was the streetwise blowhard from Philly. She hated Oscar Goodman right away. “He was just so stuck on himself, like he is,” the former Carolyn Goldmark now chuckles at the “round little Jewish boy” she met in 1960. “I thought, this guy’s just a big piece of hot air.” Both were college sophomores in Philadelphia at the time -- she at Bryn Mawr, he at Haverford. They’d both just run for student government (she won, he lost), and Carolyn’s roommate thought they might get along. “We met, and there was absolutely nothing between us -- zero,” Carolyn remembers. Two years later, after an especially galling phone call from Oscar that prompted her to hang up on him in a snit, he finally coaxed her out on a date. “He came over, just beered to the gills; and I thought to myself, I’ll never go out with this guy again. But then we met with his youngest sister, who’s a ballerina; and, somehow, that’s when I finally started to get a read on him. Then I was absolutely smitten. There are just so many sides to him. He’s just brilliant.” They married not long after -- although Oscar has a different take on their attraction. “Quite frankly, it was her legs,” he says. The skipper “Let me put it this way: In my 16 years in this town, I have never heard one bad word about Carolyn Goodman, and you can’t really say that about Oscar,” says the Ralston Report’s Jon Ralston. Adds Erin Neff, City Hall reporter for the Las Vegas Sun: “She really is a beloved person; sometimes she seems almost infallible. At the same time, she’s so politically savvy in her own right. “I get the sense that she’s been the moral conscience of that whole family, certainly in the past. Anytime you hear him talk about his religion and his faith, for example, I just get the feeling he’s talking about Carolyn’s influence.” Neff continues: “I don’t see her as a quiet, stay-at-home wife, either. I mean, after the (Jan. 9 State of the City) speech, she comes up to him and just gushes, ‘Loved it, honey; I just loved it!’ -- and she clearly meant it. “But then she says to him, ‘Can I borrow some money? I’ve got to go (to another public function)’ -- and she was gone. So I see them as two people who are still very much in love. But I also definitely see them as a power couple.” Their family teamwork, anyway, is pretty simple, according to oldest son Oscar Jr., 31, also successful Philadelphia lawyer who, like all three of his siblings, was adopted when he was three days old. And the hierarchy goes like this: Carolyn is the skipper; Oscar is the first mate -- and what Carolyn says is final. Oscar Jr. adds in an email to Las Vegas Weekly: “When I was young, (family time) was coveted. ... My mother was always present at dinnertime, and we would always discuss what important lessons of life had been learned that day.” Four decades, four kids, a bevy of mob clients, and countless adventures after the couple first met, Oscar’s picture still hangs in a discreet corner of Carolyn’s Meadows School office, where no one else can see it. “I keep him hidden in here so he’s always looking over my shoulder,” the still-smitten school founder coos. Their secret? “Truth is the key, and after truth comes respect,” she says. “You don’t really love someone without respect. Sometimes, we hate each other, like all couples; but I can tell you one thing: Our lives are never like this.” (She pantomimes a stable straight line with her right hand.) Oscar, too, rarely misses a chance to publicly compliment his spouse, whom he usually refers to as his “bride” and his “closest adviser.” Oscar is known for his raves over everything from Carolyn’s homemade chili to the gams that first caught his eye. Even Mary Hart’s celebrated legs rank only a close second, the mayor joked to the “Entertainment Tonight” star earlier this month. “In most ways, we’re so opposite; but I trust her 100 percent -- whatever she says, I have complete faith in,” Oscar says. “We rarely agree on anything, but at least I always know that her heart is in the right place, and I usually learn something important. One example was when I was running for office and she joined me in knocking on doors. I’d never done that before, but, thanks to her, I did it. And I found out very quickly how effective it can be.” Parental bribe Even when he got into the Ivy League University of Pennsylvania Law School, Carl and Hazel tried to put the reins on things. After Carolyn graduated from Bryn Mawr, they paid her way to a secretarial school in the Big Apple in exchange for her promise not to marry him for at least a year. The deal included a train ticket back to Philly every weekend. “So, I commuted,” Carolyn says. They were married in New York on a perfect late-spring day, June 6, 1962. Soon after, Oscar got a job – “because he didn't want to ask me for money,” Carolyn insists -- working for Arlen Specter, who directed appeals for the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and who would later become a U.S. senator. A fateful turn came later, when Specter asked Oscar to entertain two visiting police officers from Las Vegas. “At 2 a.m. on a horrible, rainy February night, he woke me up and said, ‘What would you think about moving to the land of milk and honey?’ And out we came,” Carolyn says. The two 25-year-olds drove cross-country in their new Cutlass convertible, shipping 37 boxes of books and a bedroom set ahead of them. They arrived at Boulder Dam with $87 in their pockets and almost nothing else. “It was August 1964; it was 120 degrees; and I made the mistake of getting out of the car -- I almost died!” she says. “I looked at my husband, and I thought, my parents were right: You married an idiot!” Oscar softened the shock by, among other things, keeping his promise to buy a horse for his riding-fanatic wife. That allowed Carolyn – who’d found a job in the Riviera advertising department -- to explore the desert on her own for hours at a time. Oscar, meanwhile, did the workaholic lawyer thing, first in the Clark County DA¹s Office, and later in private practice. Years later, Oscar started worrying about Carolyn’s safety when she rode and asked her to quit. She doesn’t seem to miss it. “Hey, I was up ‘til midnight, and working again at 3 a.m.,” Carolyn says in an interview the day after Oscar’s State of the City address. “Who has time for hobbies these days?” Rise to the top Along the way, of course, Carolyn and Oscar, had to reconcile themselves to his high-profile defense of such mobsters as Meyer Lansky and Anthony Spilotro, as well as the big-time heat it brought from the government. “Very early on in our lives together, going way back to Philadelphia, there were (defining) incidents that boiled down to, in essence, will you sell your soul to the devil to have a cushy life?” Carolyn explains. “And we came to the realization that we’d rather be poor forever, but be in control of our lives. That kind of soul-searching happened very early on.” Carolyn also advised Oscar about the distance he should keep from his sometimes-infamous clients. “When you win, I don’t mind your going out with them for a celebration -- you only pass this way once, after all,” she would tell him. “We did, too. And, I have to say that the people we met were some of most well-mannered, thoughtful, considerate people I’ve ever come across.” After another job at Caesars Palace, a UNLV counseling master’s degree in 1973, a ton of community work and almost manic fundraising, Carolyn incorporated the Meadows School in 1981. Behind only her kids and her husband, that has been her life ever since.

Sidebar By Chuck Nowlen The scene would be downright eerie if its lessons weren’t so profound: about a dozen first-graders, all in school uniforms, marching silently and single-file down a squeaky-clean, carpeted hallway. A visitor chats with the school’s founder in their path, but, even without a teacher leader, none of the kids misses a beat. As if through groupthink, the entire line veers ever so slightly as the kids approach. Now comes the kicker: “Excuse me,” each youngster murmurs, nodding, as the group almost tiptoes respectfully by. “Excuse me.” “Excuse me.” “Excuse me” -- all the way down the line. Remember, these are first-graders. Meanwhile, somewhere in the city, a public-school first-grade group is no doubt exploding in absolute hallway chaos. Which scene would you most like your child to be a part of? The answer is easy to Carolyn Goodman, who created the former when her Meadows School opened 16 years ago in Summerlin. “When I first moved here, Time magazine listed Las Vegas as one of the top five school districts in the country, but from the day we got here, it’s gone downhill,” says Goodman, a 1964 arrival with her husband Oscar, the city’s current mayor. “I spent 10 years with my kids trying to work with the district, but finally it got so frustrating that I told Oscar we had two choices -- either move or start a new school. Not that the district isn’t trying; it’s just that the package is so enormous and administration heavy.” Fueled by millions in private donations and a monster land contribution from The Howard Hughes Corp., along with the expertise of the revered late educator LeOre Cobbley, the Meadows School mirrors the training Goodman got as a child at the prestigious Brearly School in Manhattan. Manners, for one thing, are ingrained from the first day of kindergarten, and the rules of gentility apply all the way through high school. Kindergarten is also when Meadows School students start reading out loud at a podium, eating in whisper-only lunch rooms, researching scholarly papers, speaking Spanish-only four times a week, creating art, mastering timed math quizzes and computers, and learning a dawn-to-dusk, be-the-best work ethic that will stay with them for a lifetime. In sixth, seventh and eighth grade, the kids even learn Latin, just like their grandparents did, back when the world made sense. And while the Meadows School is sometimes criticized as being too whitebread, too regimented and too effete, one salient fact remains. By the time they graduate from high school, each student will be college bound: Brandeis, Harvard, Bryn Mawr, Brown -- the best schools in the nation. Oh, and by the way, the Meadows high school football team has won four state championships in a row. “This is how it should be for every kid,” says Goodman, whose school is Nevada’s only independent, nonprofit, nonsectarian, K-12 college-prep facility. Goodman remains the school’s board chair and its only college-placement counselor. She’s doggedly hands-on, too: Intense one-on-one college counseling begins in the eighth grade. Goodman’s own resume, meanwhile, is beyond reproach. Her name has been floated as a possible candidate for statewide office, and she was mentioned early on as a potential Clark County School District Superintendent last year. Those who know her well insist she would have been a great superintendent. But when Carlos Garcia got the nod, Goodman, who was never formally approached, wasn’t disappointed. “I would have had to look at it very carefully because they would have had to do it my way,” she shrugs. “I’m like my husband in that sense. I wouldn’t have let the powers that be manipulate what I would do.” Besides, she adds, she’s already got the top job at a top-shelf school that was her own brainchild. All four of her children got at least a taste of the Meadows School as it evolved; most of their teachers are still there. “Our entire program is based on things that have been absolutely verified as being successful by the test of time,” Goodman adds. And the key is not in the plush, 40-acre private campus; it’s not in the school’s bank of state-of-the-art computers, either. “Those things are great, but they don’t teach. Here, the key is the teaching,” Goodman says. “I just checked the figure, and 79 cents of every dollar here goes directly to classroom instruction.” That’s from a cream-of-the-crop, 73-person faculty that maintains a cozy 11:1 student/teacher ratio. (The ratio in some Clark County schools, legislative mandates notwithstanding, is 30:1.) The results: * A 1,281 average composite SAT score for the Meadows School class of 2001 -- verbal-655, math-626. In the Clark County School District, those numbers were 502 and 515, respectively, a combined difference of 264. * The 53-student class of 2001 included 10 first-round qualifiers for National Merit Scholarships, the highest percentage in Nevada. The year before, there were three national scholars (one as a junior); 12 Nevada State Scholars; and 10 finalist, semi-finalist or commended National Merit Scholars. * Disciplinary problems? Virtually nonexistent. Goodman attributes that, among other things, to behavior seeds that are planted early. “Whatever you can do before fifth grade is very, very important,” she says. “If you can instill that love of learning before that, the kids will be fine -- and that’s exactly what we try to do here.” Rigid or results-driven? “For our educational system ever to improve, I’m not alone in thinking that there will have to be more of the kinds of things you see at the Meadows School,” says Daniel Van Epp, president of The Howard Hughes Corp. “The whole concept is pretty rigid at the Meadows School, as far as the standards that they strive for. But the results, by almost any measure you choose, have been great, although I’d guess that some things might be just a little tougher to incorporate in a public school environment.” Supt. Garcia, of course, agrees with that last point, citing, among other things, teachers-union clout and a laundry list of state and federal mandates that affect public schools, but not private ones. He also emphasizes that the Clark County School District’s 200,000-plus enrollment dwarfs that of the Meadows School. “The fact of the matter is that they don’t have to take everybody, whereas we do,” Garcia says. “We have no other requirements other than whether you’re a citizen. “So, yes, I always feel that between public and private schools, maybe we both can learn from one another. For some kids, I’m sure a school like the Meadows is the best; but for other kids, I’d argue that some of our programs are at least as good and maybe even better in some cases.” Still, with the decline of Las Vegas’ schools apparently approaching a crisis stage in recent years, many insist that it’s time to take bold action. “Some of these things (at Meadows School) are what we should really be going back to,” says Eugene Collins, NAACP of Las Vegas executive director, for example. “And here I’m especially talking about some of the moral issues and so forth, although I’m by no means limiting myself to that. So I’m looking forward to establishing more of a dialogue with Mrs. Goodman and the Meadows School. And hopefully, we can find a way to pass some of that on down to our public schools.” Meadows School myths? Granted, the school -- a 100 percent tuition- and donation-funded private facility -- costs $6,000 a year for pre-school, $8,950 for K-5, $9,750 for 6-8, and $11,900 for high school. That’s a rough, four-school average of $9,150 per student per year. But, in view of everything Meadows School offers, maybe that’s a bargain when compared to the school district’s estimated $5,700 K-12 per-student cost this year -- especially as a move gathers momentum to privatize some 20-odd public schools by next fall. Meadows’ race and income figures also might surprise. About 15 percent of the students get a total of $600,000 in financial aid every year -- an average of about $5,000 per recipient. Meadows is about 9 percent black and about 23 percent minority -- much more diverse that the overwhelming share of Nevada school districts. In Clark County, meanwhile, the numbers are about 14 percent and 50 percent, respectively. And the much-maligned uniforms? Goodman insists they¹re about student parity, not robotic discipline. “The uniforms are required mainly because our students come from a pretty broad economic and social spectrum,” she explains. “And we don’t want any of the kids to be able to seize on that. The idea is, who cares if mom and dad are so-called successful? The uniforms are really to give all the children a feeling of equity.” Finally, the notion that all the regimentation pounds the creativity out of its students. “That’s certainly the perception,” says one of many prominent Las Vegas citizens who have considered the Meadows School for their children. “The perception is that the kids over there are kind of pod kids, that Carolyn Goodman and the administration conduct the school as a kind of military academy and breed all the personality out of them.” This one is almost guaranteed to make Carolyn Goodman bristle, albeit with characteristic grace. “These kids will be free for the rest of their lives. We don’t stifle anybody; we’re about giving them the tools to both create and enjoy that freedom,” she says. “These kids are healthy, wonderful, well-mannered and creative people who can’t get enough learning. Long after they’ve graduated, they’ll look back on the gift they got here, and they’ll realize they had no idea what a gift it was until they got out into the world. And that gift is the freedom and the ability to explore.” Besides, others note, colleges like Harvard, Yale and Stanford aren’t exactly known for recruiting intellectual sycophants. Or, as Goodman puts it later, well after the line of “excuse me” first-graders passes by and slips quietly into a classroom: “We teach to the top here. We teach the bottom, don’t get me wrong. But we teach TO the top.” |

Back To Clips |

|